“Over time, the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index has built a detailed picture of our collective sense of wellbeing, and the impact social issues and events have on this sense.”—Rohan Mead, Group Managing Director of Australian Unity.

Key points

- The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index measures personal wellbeing and national wellbeing.

- Over 20 years, Deakin University has conducted 37 nationally representative surveys with more than 65,000 Australian adults.

- National wellbeing scores tend to fluctuate more than personal wellbeing scores.

To reap the benefits of greater wellbeing, we need to measure people’s subjective evaluation of their individual, community and national wellbeing.

In doing so, we can access insights that guide government policy and practices, and use the information to promote wellbeing at all levels, advance research, and inform public health and community-level actions across Australia.

The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index uses two measures of wellbeing when surveying the population—the Personal Wellbeing Index and the National Wellbeing Index.

Associate Professor Delyse Hutchinson, the lead researcher of the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index, says it is a “particularly rigorous tool for assessing wellbeing among Australian adults”, but at the same time it’s “quite a simple measure, not very complex”.

Delyse says that it’s important that we measure both personal and national wellbeing: “When we look at the Personal Wellbeing Index alongside the National Wellbeing Index, we get a more comprehensive picture of wellbeing for the individual, the community and society.”

Personal Wellbeing Index

Personal wellbeing relates to an individual’s satisfaction with their own life. This satisfaction is measured by assessing the seven core domains of wellbeing, including what we refer to as the “golden triangle of happiness”—relationships, achieving in life and standard of living—which are the three areas that most significantly impact on our wellbeing.

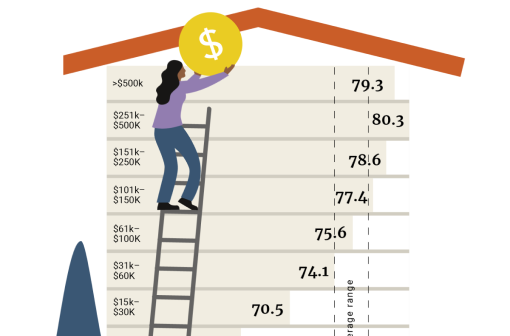

By conducting surveys over time and using different demographics from the community, we can examine how age, income, relationship status and other factors affect our sense of personal wellbeing.

National Wellbeing Index

National wellbeing relates to our satisfaction with our life in Australia. To work out the national wellbeing score, we measure satisfaction with the economic situation, the natural environment, social conditions, the government, business and national security.

20 years of wellbeing

Over 20 years, Deakin University has conducted 37 nationally representative surveys with more than 65,000 Australian adults across the country. Australians in metropolitan, regional and rural communities have been surveyed.

“Over time, the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index has built a detailed picture of our collective sense of wellbeing, and the impact social issues and events have on this sense,” says Rohan Mead, Group Managing Director of Australian Unity.

“It tracks how we feel about our relationships, finances and our broader purpose in life. So, too, we have gauged the nation’s satisfaction with economic, business and social conditions, government, national security and the environment.”

Interestingly, says Delyse, personal wellbeing in Australia has remained relatively stable over this period.

“I think there are a couple of reasons for that. First and foremost, we live in a very good community. We have a fundamentally civil society that looks after its citizens and provides health and other services, and financial support to those in need.”

The other factor that helps people bounce back from challenges is a process called homeostasis, which tends to bring us back to a rough set point for wellbeing after we experience highs and lows.

The power of homeostasis was demonstrated during the 2020 survey, which took place just after Australia’s devastating bushfire season and in the middle of the nation’s first COVID-19 lockdown.

Despite these events, personal wellbeing scores remained in the average range.

National wellbeing, on the other hand, doesn’t have this same anchor point, which means scores tend to fluctuate more.

We tend to see “ebbs and flows” depending on what’s going on, and as a result, national wellbeing scores tend to be about 14 points lower than personal wellbeing scores.

Some of the biggest events of the past 20 years that have affected national wellbeing scores include the global financial crisis, the bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“World or local events can impact on wellbeing,” says Delyse. “Take the global financial crisis for instance, where we saw a drop in people’s satisfaction with the economic situation.”

Interestingly, while the adversity faced by Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic might have been expected to result in a decrease to national wellbeing, the 2020 survey saw national wellbeing move out of its average range to reach its highest score in 20 years—potentially due to the availability of resources such as the JobKeeper payment, and a sense that Australia was “doing better” than many other countries.

Homeostasis: our in-built wellbeing protector

Just as our bodies have a natural ability to maintain body temperature within a certain range, we also have in-built mechanisms to regulate our emotional functioning.

This theory of wellbeing homeostasis explains why personal wellbeing scores are relatively stable over time.

As we experience joy, frustration, anger, sadness and other emotions, a background mood—called Homeostatically Protected Mood (HPMood)—eventually wins out and pulls us back to a baseline of contentment.

Of course, the stronger the emotion we are experiencing, the more difficult it can be for homeostasis to pull us back to HPMood—but internal and external resources can help to provide balance.

Optimism, confidence and a sense of control over our life are internal resources that help to power wellbeing homeostasis, while financial stability and a social support network are examples of external resources that can play a part in this crucial regulation process.