“No generation is happy with the direction our country is going in.”—Dr Kate Lycett, Australian Unity Wellbeing Index lead researcher, Deakin University

Key points

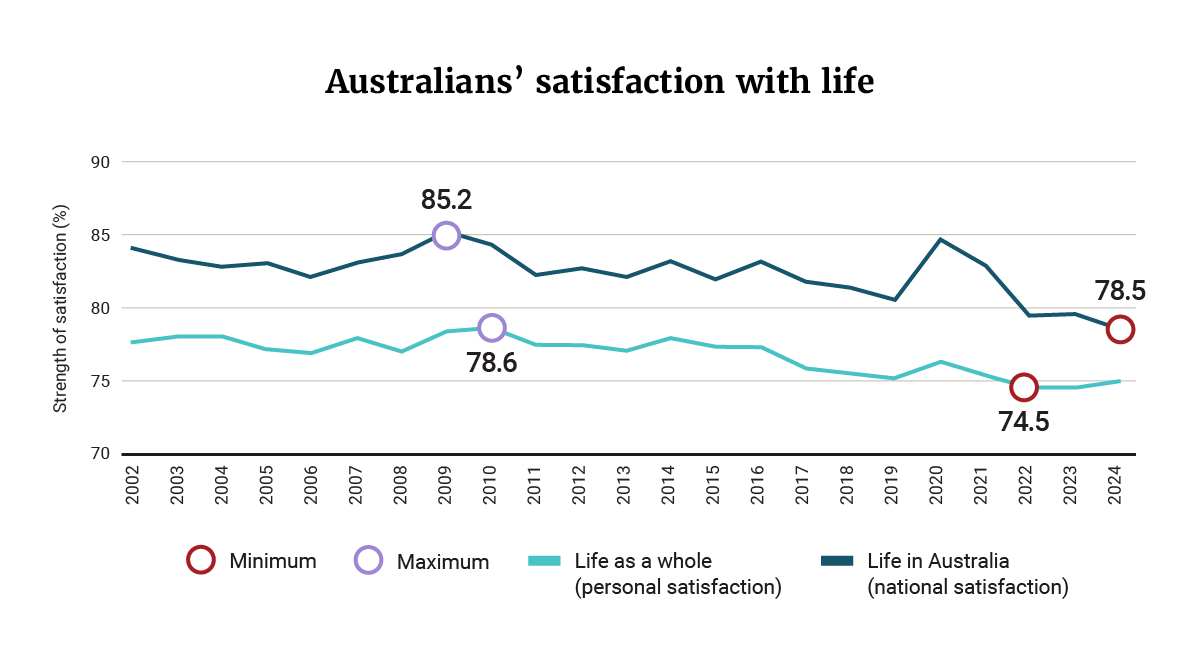

- This year’s Australian Unity Wellbeing Index shows that our satisfaction with life in Australia has hit an all-time low.

- Our national wellbeing is also at a record low, driven by plummeting satisfaction with the economy.

- This dissatisfaction potentially reflects inequities in wealth and social mobility, a growing sense of division, and a declining sense of connection.

From a distance, Australia is widely considered to be one of the most enviable countries to live in the world. The international stereotype is of a nation that enjoys magnificent beaches, plenty of sunshine and routinely excellent coffee. Our lifestyle is revered for its comparatively laid-back pace and proudly egalitarian nature.

In 2024, that glowing reputation was further enhanced by a new study comparing the life expectancy among six high-income, English-speaking countries. It found that Australians not only lived the longest—a position we’ve retained since the early 1990s—but that we also enjoyed the lowest level of “geographic inequality”, which means the gap in life expectancy between rich and poor areas is narrower than any of our surveyed peers.

Yet scratch the surface and a radically different picture emerges.

Plummeting satisfaction with life in Australia

The latest research from the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index—a 24-year study into the wellbeing of Australians, conducted in partnership with Deakin University—shows that our population is increasingly unhappy with the state of the nation. When asked how satisfied they were with life in Australia, respondents’ scores were the lowest in the history of the Wellbeing Index—a timeframe that, let’s not forget, included a global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Drilling deeper, the research also tracked the National Wellbeing Index, which measures our satisfaction across six key domains of national life. This score also dropped to unprecedented levels in 2024, with declining satisfaction with the state of our government, business and national security. Meanwhile, satisfaction with the economy plummeted even further beyond the all-time low score recorded last year.

What’s notable is that while personal wellbeing scores—which reflect our satisfaction with domains such as our relationships, health and “standard of living” (finances)—varied across different age groups, these low national wellbeing scores were uniform across the various age demographics. “That shows that no generation is happy with the direction our country is going in,” says Australian Unity Wellbeing Index lead researcher Dr Kate Lycett, from Deakin University’s School of Psychology.

The impact of increasing inequities

Kate believes the root of the problem is the growing inequities that are killing the opportunities for social mobility that Australians have traditionally held so dear.

“We’re at a time where the cost of living has become so great and wage growth hasn’t kept up. That’s having a really big impact on how we’re doing as a nation,” says Kate. “The wealth inequities are huge and we are not doing anything to address those.”

That issue is most starkly visible in housing prices that are increasingly out of reach for those on average incomes. “If you don’t feel like you can get ahead unless Mum and Dad can buy your house or pay for your house deposit, then you’re in real trouble in Australia at the moment. And that’s not the kind of society we want,” says Kate. “Older people are aware of it, too. They don’t want their children or grandchildren to be in a situation where it’s impossible to buy a house.”

A fractured society

Adam Vise leads the Treasury, Strategy and Impact teams at Australian Unity, a role that involves considering how to maximise the social impact of the company’s wellbeing initiatives. Reflecting on the growing sense of negativity in Australia, he points out that many countries around the world are battling similar woes in terms of soaring inflation and the rising cost of living. “There seems to be quite a lot of evidence that this dissatisfaction is happening simultaneously in many high-income companies,” he says.

Yet what concerns Adam is the growing sense of division as Australia becomes increasingly tribal and fractured. “The dispersion of opportunity is starting to break down,” he says. “The young are starting to really disengage and lose hope, which is unprecedented. For me, that’s fundamentally the biggest worry.”

Much of this fracture is playing out across generational divides. The growing wealth of baby boomers over the last 30 years has largely stemmed from steadily climbing house prices, a rise in Australian equities and a tax system that’s supported property investment through policies such as negative gearing.

“The boomers have had a very good run, and the system designed by them continues to serve them,” says Adam. “But the next generation are starting to see there’s not as much opportunity.”

A lack of connection

A parallel issue, Adam suggests, is that Australian society has become increasingly disconnected.

There are numerous causes behind this, from the decline in religious participation to the impact of the internet and social media, which encourages many of us to spend more time alone, glued to our private screens. These disparate factors were compounded by the trials of COVID, which forcibly exacerbated our lack of community connectedness. The upshot is an epidemic of loneliness that’s particularly rife among young Australian adults.

“We know that the real pathway to great wellbeing is to be really connected in your life to friends and family and to the community at large,” Adam says. “I think there’s a huge need and opportunity for people to get together and try to help each other out.”

Disclaimer: Information provided in this article is of a general nature. Australian Unity accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of any of the opinions, advice, representations or information contained in this publication. Readers should rely on their own advice and enquiries in making decisions affecting their own health, wellbeing or interest. Interviewee titles and employer are cited as at the time of interview and may have changed since publication.

.jpg)

.jpeg)